Carol writes: On leaving The Bend/Sisters area, we drove 150 miles south to a small family campground in Prospect, Oregon.

Prospect was in such a remote area in south central Oregon that we had to head into “town” to the community library to get cell phone reception.

However, the campground WiFi was great, and our rig was situated so that we were able to get satellite TV reception half under a canopy of very tall Douglas-fir and Ponderosa pines… so, all things considered, we were the proverbial happy campers.

There really was only one reason we had decided to visit Prospect, Oregon, and that was for the chance to revisit Crater Lake.

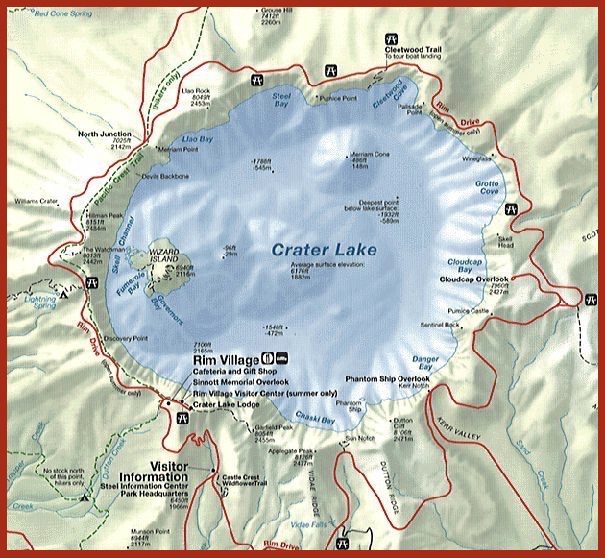

The history of Crater Lake is a tale of great geologic turmoil. Approximately 7700 years ago, the largest volcanic eruption in a million years within the Cascade Volcanic Arc blew 6000 feet off the top of what was then 12,000 foot Mount Mazama. This massive explosion resulted in a deep basin (caldera) that slowly filled with rainwater and snowmelt. Future smaller eruptions sealed the crater floor, and thus Crater Lake was born…

During our family year of travel in 1989, two attempts to visit Crater Lake were on days when every view of the lake was shrouded in clouds and fog, only leaving us to wonder what all the hype was about. Several years later during a quick trip through Oregon, the weather was cooperative and so we did make a very brief stopover at one viewpoint on the lake. We were astounded at the glorious view… and always wished we could come back for a time when we could linger.

After a summer during which wildfire smoke hung over Crater Lake for days on end, we were finally blessed with a day of near-perfect conditions for doing the 33-mile rim drive around the lake.

Heading counterclockwise on the rim, our first viewpoint was of the ghostly so-called “phantom ship,” which in reality was actually a small island of very old erosion-resistant lava, the oldest exposed rock within the caldera.

A brief detour down to “Pinnacles Overlook” revealed “fossil fumaroles” that were formed when volcanic gases ascended up through layers of volcanic ash, cementing the ash into spooky rocky pillars.

As we circled the rim and the midday sun gained ground in the sky, the blue color of the lake became more intense.

By noon, lighting conditions were perfect…

One of the most iconic views of Crater Lake is the one of Wizard Island, which was formed by a subsequent eruption within the caldera.

Wizard Island is actually a cinder cone that rises 2700 feet from the caldera floor, with only the top 700 feet visible above the surface of the lake. Yet, from the rim, the trail to the top of the cone looked like little more than a 10-minute scamper; in fact, the park newspaper touts the trail to the top as being more like a 45-minute climb.

The gigantic scale of 6-mile wide Crater Lake was strangely deceptive from the rim above…

Crater Lake holds the record for being the deepest freshwater lake in the United States, with an official depth of 1943 feet. The sublime intense blue color is due to the fact that the shorter violet and blue wavelengths of the light spectrum are the least readily absorbed in Crater Lake’s clear deep water. As a result, the blue end of the light spectrum is the dominant color reflected back at our eyes.

At the conclusion of our rim drive, the lake at Rim Village was the most magnificent shade of royal blue we had ever seen.

On the path to the historic Crater Lake Lodge,

this furry creature appeared pretty content to call Crater Lake its home.

TIONESTA, CALIFORNIA

As summer faded into fall,

our southern trajectory steered us across the state line back into California, where we settled into a very small rural campground in Tionesta, California.

Tionesta was officially a “ghost without a town,” as there was a surprising lack of much evidence that a town had ever existed, although one actually did during the heyday of the logging era. However, we eventually found plenty of interest to keep us occupied for a week in this lonely countryside...

Twenty-five miles away, just outside of the town of Tulelake, we stopped along the highway to check out what was left of the Tule Lake Segregation Center,

which was commandeered in 1942 by Franklin Roosevelt for the purpose of housing prisoners of war in addition to segregating so-called “troublesome” Japanese Americans who had been forcefully removed from their homes. This remote agricultural region, with little in the way of amenities, was a particularly harsh incarceration for up to 18,000 innocent Japanese Americans who were deemed “disloyal” because they refused to sign a deeply flawed “loyalty questionnaire.”

In northern California at the southern end of the Cascade Volcanic Arc lies Medicine Lake Volcano, the most massive mountain in the Pacific Northwest and home to over 200 cones, craters, and other volcanic landforms.

Practically within sight of our campground, within the gently sloping Medicine Lake shield volcano, was Glass Mountain. The last eruption 950 years ago resulted in the build-up of a large dome of pumice mixed in with black volcanic glass known as obsidian.

Crude roadways, smoothed over back in the days when the site was mined for pumice, made hiking easy.

Dazzling glossy obsidian attracted our attention.

Pumice boulders were impressive for their surprising lightness.

We had been advised to check out Medicine Lake, so named by Native Americans because of the touted therapeutic effect of its waters. The lake was a pleasing small version of Crater Lake,

but it was the Medicine Lake lava flow, just a short walk from the edge of the campground, which was most dramatic.

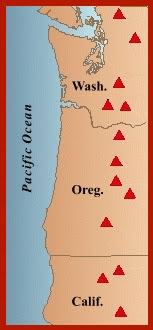

The subduction of the Juan de Fuca and Gorda plates beneath the North American continental plate has given rise to the Cascade Mountain Range. The massive tension of opposing tectonic plates has caused rock deep within the Earth to melt and erupt as lava all along the Cascade Volcanic Arc.

Lava Beds National Monument formed over thousands of years as a result of multiple lava eruptions, creating a landscape of tortuous lava caves and flows. The lava caves are one of the chief attractions for tourists.

Mushpot Cave was just the sort of paved cave experience we were willing to take on.

But Skull Cave was the winner! We welcomed Nature’s air conditioning which rose from deep within the bowels of the cave and poured out of a sizable cave entrance.

The volcanic rocks lining this substantial lava tube looked like a Disney creation.

We went as far as natural light allowed…

Back up on terra firma, we opted to make the 500-ft climb to the fire lookout at the top of Schonchin Butte cinder cone. Rabbitbrush heralded sensational fall color

on the approach to the tiny fire lookout that was anchored into a mammoth chunk of lava.

As we had anticipated, the bird’s-eye view from the top was exceptional. We were able to appreciate the extent of the Schonchin lava flow,

and this was our clearest vista to date of majestic Mount Shasta.

One of the most interesting aspects about visiting Lava Beds National Monument was the story that played out where geology met history. Over the winter and spring of 1872-73, during the Modoc War, US cavalry troops under General Edward Canby attempted to return several dozen Modoc warriors and their families to the reservation that they had been exiled to near present-day Klamath, Oregon. The end of this sad chapter played out in a section of the monument known as Captain Jack’s Stronghold.

Captain Jack was the name given to Modoc Indian chief Keintpoos, who along with 60 of his warriors and their families had retreated to his stronghold in the lava beds along the banks of the Tule River in what is now the northern part of the park. For three months Captain Jack and his warriors heroically held off Canby’s cavalry, until the Army cut off the Modoc water supply and resistance became impossible. Army forces eventually captured Captain Jack’s Stronghold, although most of the Modoc people had mysteriously escaped undetected during the night.

The trail through Captain Jack’s Stronghold was very enlightening.

Captain Jack’s Modoc warriors had a decided advantage in the rugged volcanic terrain that they knew so well. Narrow protective passageways and small caves were part of the natural fortress that allowed the Modoc to repulse an Army force 6 times its size.

Along the trail, the Modoc medicine flag, adorned with symbols of appreciation that had been left by visitors, was most touching.

Canby’s Cross, a few miles down the road, was a memorialization to General Canby, who was killed by Captain Jack during peace negotiations, a crime for which he was later hanged along with three other Modocs.

The inscription on the cross illustrates that the Army considered General Canby’s shooting to be murder, whereas from the Modoc point of view, the shooting was considered a justifiable tactic of war.

In summary…

The tremendous geologic turmoil that created diverse volcanic features at Crater Lake and Lava Beds National Monument was a fascinating narrative on a grand scale. Additionally, however, other stories where history met geography were the ones that touched our conscience. Tule Lake Segregation Center symbolized shameful disregard for constitutional rights of Japanese Americans. Likewise, the horrible indifference to Native American rights that played out at Lava Beds illustrated the tragic consequences of widespread forced banishment of Native American tribes to bleak reservations far from their revered homelands.

No comments:

Post a Comment